Adventures in social distancing

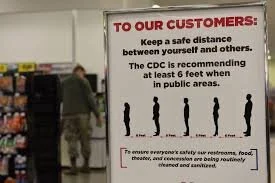

In a world where being around other people can feel frightening, social distancing recommendations by the WHO and CDC are vital ways to protect ourselves and others. My partner and I are white-collar workers living in Downtown Los Angeles. While social distancing feels manageable in concept, we've found that, in reality, our world is not built to maintain two arms length away from other people.

Today marks two weeks since we shut the rest of the world away and holed up in our Downtown L.A. flat. Just a few days before our voluntary lockdown, we had traveled from Los Angeles to Bodega Bay on a coastal road trip with my mother. When we returned to Los Angeles, we decided to isolate ourselves from our family and community members until we could be sure we were not infected. Meanwhile, Governor Gavin Newsom gave the nation's first statewide order to stay at home, further reinforcing our decision.

So far, so good, as we remain symptom-free, but our two weeks of self-isolating hasn't allowed us to be risk-free. Between groceries, picking up packages, and the few times we've left our apartment for essential trips, we've learned just how hard it is to protect ourselves and those around us via social distancing.

For all their claims, companies are not providing adequate social distancing training for their essential workers

We are exceedingly grateful for every essential worker. These are workers who have historically been denied livable wages and humane benefits. Still, even in peacetime, hospitals can't run without janitors to clean them, and the real standing ovation should always have gone to grocery workers who are staples of every community.

Like many others, we've turned to deliveries for our essential items. We've received three grocery deliveries and ordered many other supplies and quarantine activities that we might have previously gone to a store to buy.

This weekend Instacart and Amazon workers announced they would strike, and some have walked off the job. Although our email inboxes have been flooded with Covid-19 information emails from companies insisting they're protecting workers and consumers with contactless deliveries and enhanced social distancing policies, the reality has fallen considerably short.

As there has been no advice given to citizens about how many supplies they should have, we, like so many others, wanted to build up around two weeks worth of dried and fresh goods in case of sickness or more extreme quarantine measures.

In our two orders from Whole Foods, I had to sign the delivery persons' iPhone to receive my groceries. Although I did my best to maintain at least 6 feet from the delivery people, because of needing to sign the device, neither Amazon delivery person was able to be equally cautious.

A similar situation occurred when we needed to sign for a package from UPS whereby the UPS worker not only did not social distance, but asked us to use a communal pen to sign for the package.

Signing for card payments and other, close quarter interactions, are taken for granted in the modern world but large companies are in charge of innovating in this sector. We're seeing first hand how companies are failing to adapt processes for this unprecedented crisis. The workers, who are essential not just in a time of crisis, but always, are the first victims. They deserve better training and protection from their employers about how to navigate this changing world.

In addition to personal protective equipment, it's clear that more training and empowerment needs to trickle down to workers so that they're physically protected and have the skills to overcome potentially harmful situations, which could happen at any delivery.

What I've learned about social kindness when socializing equals fear

It has become common to see glances of fear and flight amongst people with whom we come into contact. How do we exist in common spaces without coming too near each other? How do we ask people or tell people to maintain 6 feet away from us? How do we practice compassion in a time when we want to say to others: get away from my family.

The first thing we can all do is remember that these guidelines are new, and it takes time to train our neural networks to make space around us for other people and override muscle memory of standing close together.

My partner and I stopped at the Follow Your Heart market and cafe when Los Angeles only had a few hundred Covid-19 cases, and as we stood in line, another, older, customer stood closely behind us.

I had to overcome the initial pound of fear for myself, my partner, and this older person to turn around, with a smile, and say: "We are practicing social distancing, would you mind standing just a few feet further away from us?"

She stepped a few more feet away and replied, "Oh, I am too. It's just hard to remember."

I thanked her, but in hindsight, I also wished I had asked this woman how she was faring in this changing world. Kind reminders to adhere to social distancing can ripple outward, helping us change our behavioral patterns, but also create positive social interaction in a time of social fear.

Even when we finally train ourselves to physically distance, other people can feel like ticking time bombs. Is that person going to get too close to me? What if the elevator opens and someone else tries to get in? Or, that person clearly hasn't explained social distancing to their child.

Before beaches around Los Angeles closed, we took a long walk along the shore in Malibu, taking extra care to walk 6-10 feet around people. As we walked, families with young children would observe us in fear that we might get too near to them, and although the beach was quite empty, apprehension was palpable.

When we're vectoring, again, we should be clear and kind in our intentions. It feels strange and, perhaps, even overkill. At one point, we encountered a family with a young boy who ran back and forth between his dad in the water and his mom on the beach. As we approached the family, doing our best to steer clear of the child, his dad told him to run up to his mom, and, of course, he turned around and ran back to his dad, putting him well within 6 feet of us.

We could have solved that interaction by clearly stating that we would walk up and around their family or asking the father to let us know when we could pass.

Fear and apprehension of other people are new and will be around for some time as many health experts have predicted we may be in social isolation for months to come. It is our job to protect ourselves and those around us, especially our essential workers, requiring new practices for engaging with the world. These clarifying tools should become our new best friends.

Companies should be coaching and training essential workers in them every day. They should update their standards to ensure that no one has to touch a communal pen or iPhone. Essential workers are human beings; they are not disposable. We must remember and maintain our humanity this time of confusion and fear.

Building new rules of social engagement and redefining our role in executing those rules are essential ways we can maintain kindness and compassion in a time of uncertainty.